588 BC: Traditional start date for Nebuchadnezzar II’s siege of Jerusalem, which steadily tightens the noose around the Jewish

1412: The Medici family of Florence is formally appointed to act as banker to the Papacy, an account that greatly accelerated their rise as the most powerful family in Italy, to say nothing of hastening the development of modern banking and accounting methods to accurately deal with vast sums of money.

1493: From his anchorage off the Caribbean island of

1559: Coronation of Elizabeth I as Queen of England.

1707: The Scottish Parliament ratifies the Act of Union with England, beginning the process of creating the United Kingdom of England, Scotland and Wales (and later, Northern Ireland). Interestingly, back in January 2011, the Scottish Parliament decided to hold a plebiscite on the de-ratification of the Act of Union, in order to make Scotland an independent country within the EU. The independence vote was finally taken in September of 2014 and was handily defeated 54/46, with a historically high turnout of 85% of the electorate making their voices heard.

1759: Opening day for the British Museum.

1761: Great Britain captures Pondicherry, India from its former French overlords. Despite coming under British rule from this point, the city never lost its French colonial flavor. It served culturally as a competitive rival to Bombay and Calcutta, both of which were under British influence from the early days of the East India Company.

1784: The new United States government ratifies the Treaty of Paris, which acknowledges its existence as an independent political entity.

1741: Birth of Benedict Arnold (d.1801).

1786: The Virginia General Assembly accepts the Virginia Statute of Religious Freedom, written by Thomas Jefferson– as part of the supreme law of the Commonwealth. Jefferson was so pleased with this concise document that he insisted it be included in his epitaph.

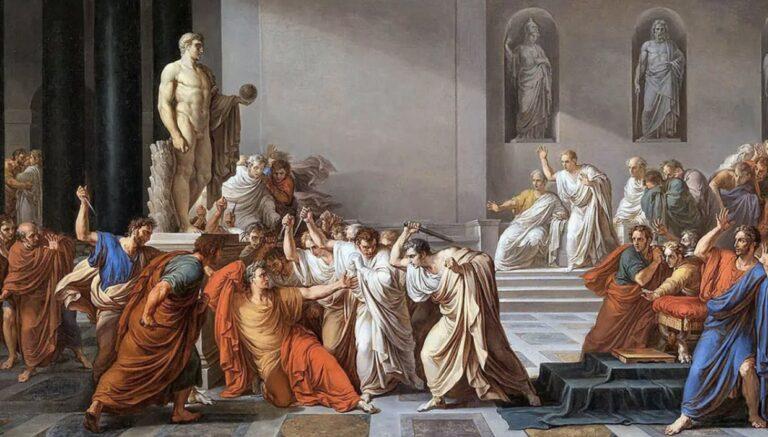

1794: Death of British historian and man of letters, Edward Gibbon (b.1737), best known for his seminal work, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. His research and subsequent publication of this true magnum opus sets the standard for scholarly work to this day.

1815: The frigate USS President, under the command of Commodore Stephen Decatur, is captured by a squadron of four British frigates as it tries to break out of its year-long blockade of New York harbor.

1875: Birth of Albert Schweitzer (d.1965), musician, theologian, and medical doctor whose work in easing the lives of African tribesmen in Gabon, and his deep intellectual response to the real problems of both colonialism and the de-colonizing movement earned him the Nobel Peace Prize in 1952.

1889: In Atlanta, incorporation of the Pennington Medicine Company, which became famous and wealthy from their premier retail product, Coca-Cola.

1902: Birth of Scottish runner and Christian missionary to China, Eric Liddell (d.1945). He is the protagonist of the Academy

1919: Death of Rosa Luxemburg (b.1871), a fiery Marxist absolutist who played a crucial role in agitating German workers during the 1918 revolution, through her pamphleteering and communist agitation in the immediate aftermath of the Great War. With the functional dissolution of the German government, bands of vigilante enforcers known as the Freicorps roamed the cities and countryside, enforcing a harsh German nationalism against the untrammeled influences of outside forces. As a particularly blatant exemplar of those outside forces, Rosa Luxemburg found herself increasingly harassed by the Freicorps and finally on this day, she was arrested, tortured, and murdered- her corpse thrown into the Landwher Canal for good measure. Since her death, the international communist movement has worked to beatify her as a martyr for the Marxist-Socialist movement.

1929: Birth of Civil Rights activist and Baptist preacher, Martin Luther King, Jr.

1932: Birth of Don “Big Daddy” Garlits. A pioneer in the field of drag racing, he perfected the rear-engine Top Fuel dragster, an innovation motivated by the loss of part of his foot in a dragster accident.

1938: Norway formally annexes for itself a huge slice of Antarctica, naming the area Queen Maude Land. It remains the only du jure territorial occupation on the continent, although the rest of it is divided up between six other claimants and multiple non-claimants (including the U.S. and Russia) who maintain permanent scientific stations above and below the ice.

1943(a): After over 6 months of brutal combat and continuing losses to the U.S. Marines, the Japanese army completes Operation KE, the evacuation of Guadalcanal, which they consider a great success.

1943(b): First day of the Casablanca Conference between President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill with representatives of the Free French forces. Joseph Stalin was invited but declined to attend because of the ongoing siege of Stalingrad. This conference was notable for publicly declaring unconditional surrender as the core Allied war aim against Germany. The decision was also made to not attempt to open a second European front via cross-channel invasion, but to continue the pressure on the southern flank by invading Sicily. As an aside, in order to get to the conference, Roosevelt became the first President to fly in an airplane while serving in office, taking a plane between Miami and Casablanca across the Atlantic Ocean.

1943(c): Opening day for The Pentagon, at the time and for decades afterward, the world’s largest office building. The building remains a uniquely functional space; despite its size, a normal person can walk from any office to any other in 12 minutes or less. Its hubs and spokes provide for a straightforward office numbering system and the courtyard in the middle provides a very nice respite from the cube-farm world inside.

1950: First flight of the prototype MiG-17 fighter plane, a workhorse of the communist bloc through the 1980s.

1991: At midnight local time, the United States-led coalition opens fire in Operation Desert Storm. President George H.W. Bush, in his Address to the Nation, puts it very simply: “The liberation of Kuwait has begun.”

2001:Wikipedia goes on line.

I have taken the time to read The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire by Gibbon, which was one of the the books that the western author Louis L’Amour recommended reading if you wanted to educate yourself.

Gibbon also wrote essays, one of which was “General Observations on the Fall of the Roman Empire in the West,” where Gibbon stated as follows:

The Greeks, after their country had been reduced into a province, imputed the triumphs of Rome, not to the merit, but to the FORTUNE, of the republic.

The inconstant goddess, who so blindly distributes and resumes her favours, had now consented (such was the language of envious flattery) to resign her wings, to descend from her globe, and to fix her firm and immutable throne on the banks of the Tiber.

A wiser Greek, who has composed, with a philosophic spirit, the memorable history of his own times, deprived his countrymen of this vain and delusive comfort by opening to their view the deep foundations of the greatness of Rome.

The fidelity of the citizens to each other, and to the state, was confirmed by the habits of education and the prejudices of religion.

Honour, as well as virtue, was the principle of the republic; the ambitious citizens laboured to deserve the solemn glories of a triumph; and the ardour of the Roman youth was kindled into active emulation, as often as they beheld the domestic images of their ancestors.

The temperate struggles of the patricians and plebeians had finally established the firm and equal balance of the constitution; which united the freedom of popular assemblies with the authority and wisdom of a senate-and the executive powers of a regal magistrate.

When the consul displayed the standard of the republic, each citizen bound himself, by the obligation of an oath, to draw his sword in the cause of his country, till he had discharged the sacred duty by a military service of ten years.

This wise institution continually poured into the field the rising generations of freemen and soldiers; and their numbers were reinforced by the warlike and populous states of Italy, who, after a brave resistance, had yielded to the valour, and embraced the alliance, of the Romans.

The sage historian, who excited the virtue of the younger Scipio and beheld the ruin of Carthage, has accurately described their military system; their levies, arms, exercises, subordination, marches, encampments; and the invincible legion, superior in active strength to the Macedonian phalanx of Philip and Alexander.

From these institutions of peace and war, Polybius has deduced the spirit and success of a people incapable of fear and impatient of repose.

The ambitious design of conquest, which might have been defeated by the seasonable conspiracy of mankind, was attempted and achieved; and the perpetual violation of justice was maintained by the political virtues of prudence and courage.

The arms of the republic, sometimes vanquished in battle, always victorious in war, advanced with rapid steps to the Euphrates, the Danube, the Rhine, and the Ocean; and the images of gold, or silver, or brass, that might serve to represent the nations and their kings, were successively broken by the iron monarchy of Rome.

The rise of a city, which swelled into an Empire, may deserve, as a singular prodigy, the reflection of a philosophic mind.

But the decline of Rome was the natural and inevitable effect of immoderate greatness.

Prosperity ripened the principle of decay; the causes of destruction multiplied with the extent of conquest; and, as soon as time or accident had removed the artificial supports, the stupendous fabric yielded to the pressure of its own weight.

The story of its ruin is simple and obvious; and, instead of inquiring why the Roman empire was destroyed, we should rather be surprised that it had subsisted so long.

The victorious legions, who, in distant wars, acquired the vices of strangers and mercenaries, first oppressed the freedom of the republic, and afterwards violated the majesty of the purple.

The emperors, anxious for their personal safety and the public peace, were reduced to the base expedient of corrupting the discipline which rendered them alike formidable to their sovereign and to the enemy; the vigour of the military government was relaxed, and finally dissolved, by the partial institutions of Constantine; and the Roman world was overwhelmed by a deluge of Barbarians.

The decay of Rome has been frequently ascribed to the translation of the seat of empire; but this history has already shewn that the powers of government were divided rather than removed.

The throne of Constantinople was erected in the East; while the West was still possessed by a series of emperors who held their residence in Italy and claimed their equal inheritance of the legions and provinces.

This dangerous novelty impaired the strength, and fomented the vices, of a double reign; the instruments of an oppressive and arbitrary system were multiplied; and a vain emulation of luxury, not of merit, was introduced and supported between the degenerate successors of Theodosius.

Extreme distress, which unites the virtue of a free people, embitters the factions of a declining monarchy.

The hostile favourites of Arcadius and Honorius betrayed the republic to its common enemies; and the Byzantine court beheld with indifference, perhaps with pleasure, the disgrace of Rome, the misfortunes of Italy, and the loss of the West.

Under the succeeding reigns, the alliance of the two empires was restored; but the aid of the Oriental Romans was tardy, doubtful, and ineffectual; and the national schism of the Greeks and Latins was enlarged by the perpetual difference of language and manners, of interest, and even of religion.

As the happiness of a future life is the great object of religion, we may hear, without surprise or scandal, that the introduction, or at least the abuse, of Christianity had some influence on the decline and fall of the Roman empire.

The clergy successfully preached the doctrines of patience and pusillanimity; the active virtues of society were discouraged; and the last remains of the military spirit were buried in the cloister; a large portion of public and private wealth was consecrated to the specious demands of charity and devotion; and the soldiers’ pay was lavished on the useless multitudes of both sexes, who could only plead the merits of abstinence and chastity.

Faith, zeal, curiosity, and the more earthly passions of malice and ambition kindled the flame of theological discord; the church, and even the state, were distracted by religious factions, whose conflicts were sometimes bloody, and always implacable; the attention of the emperors was diverted from camps to synods; the Roman world was oppressed by a new species of tyranny; and the persecuted sects became the secret enemies of their country.

end quotes

One must wonder if there is anything for us in this country today in all of that.