1093: Dedication of Winchester Cathedral, the nominal home of King Arthur’s round table.

1388: An army of Swiss soldiers, outnumbered 16:1, defeats a Hapsburg army of over 6,500 in the Battle of Nafels, an astounding rout by about 400 armed citizens of the cantonment of Glarus and a handful of knights from other parts of Swiss* Confederation. The battle was the final act in the long-running conflict between the ever-expansionist Hapsburg Empire and the ever-stubborn and independent minded farmers and shop keepers of the central Alps. After this battle, the Swiss kept their independence and the Emperor decided to leave them alone.

1413: After five years of increasingly bitter fighting with the Welsh, the 27 year old Henry of Monmouth is crowned King Henry V of England on the death of his father, Henry IV. The young king almost immediately turned his attentions to regaining historic landholdings in France against the Valois dynasty, to say nothing of living out a life that inspired William Shakespeare to some of his finest work.

1585: Departure from England of a five-ship fleet, organized and funded by Sir Walter Raleigh, to create a permanent English colony in the New World. The group eventually landed and set up camp on the shores of Roanoke Island on North Carolina’s Albemarle Sound. The little settlement maintained a tenuous toehold on the land; between conflict with the local Indian tribes, and lack of a viable means to sustain their need for food, the success of the enterprise was very much on the edge of maintaining viability. Raleigh commissioned his friend J0hn White two years later to go back to Roanoke with a small fleet for re-supply and reinforcement, including 115 more colonists. When they arrived they found no one except a bleached out skeleton. White stayed long enough to help the new group get re-established, and promised to return with more supplies the following Spring. Multiple delays- war, piracy, hurricanes…the usual- intervened, and when he finally stepped ashore in August of 1590, not a trace of the new colony could be found. The only clue was the word “CROATOAN” carved into a tree, and the letters “CRO-” in another. The Lost Colony remains lost to this day, but it fuels a vibrant tourism economy down in the Outer Banks. After the English colonies actually did take hold up and down the coast, there were for years reports of blue-eyed Indians who inhabited the tidewater regions of North Carolina and Virginia colonies, providing some degree of explanation about the fate of the little colony.

1588: Birth of English philosopher Thomas Hobbes (d.1679). He is probably best known for his rather gloomy view of the human condition and the need for a powerful sovereign to maintain order. In his magnum opus, Leviathan (1651), Hobbes described life of an unconstrained individual in a state of nature as “…solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short.”

1606: King James I grants a royal charter to the Virginia Company of London, a joint stock company that will finance British colonization of North America north of Cape Fear

1614: Virginia native Pocahontas marries British subject and Jamestown leader John Rolfe.

1621: After wintering over in Cape Cod Bay, Mayflower sets sail from Plymouth, Massachusetts on its return trip to England.

1730: Dedication of Shearith Israel- the first synagogue in NYC.

1778: Commanding his brig USS Ranger, Captain John Paul Jones departs Brest, France on a raiding mission against British interests in the Irish Sea. It is the first offensive naval action of the American Revolution, and the attacks take the British completely by surprise. In a particularly daring raid into his native Scotland, Jones sails into Kirkcudbright Bay with a view to abduct the Earl of Selkirk and hold him hostage for the release of American sailors held by the British. The earl is not at home but the crew takes the liberty to steal his silver, including his wife’s teapot, still warm and full of her morning tea. The raids continue for several more weeks, and after capturing HMS Duke, Jones returns to Brest where he will seek a larger ship and make plans for more raids as the year progresses.

1792: President Washington issues the first presidential veto on a bill concerning apportionment of representatives between the several states.

1794: Birth of Rear Admiral Matthew Perry

1820: Venus de Milo (b.130 BC) is discovered on the Greek island of Melos, and is promptly transported to Paris for public display at the Louvre.

1849: Walter Hunt of New York patents the safety pin. He later sells the rights for $100.

1865: After his Appomattox meeting [DLH 4/9] with Union Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, Major General Robert E. Lee, CSA, issues General Order #9, his last:

“After four years of arduous service, marked by unsurpassed courage and fortitude, the Army of Northern Virginia has been compelled to yield to overwhelming numbers and resources. I need not tell the brave survivors of so many hard-fought battles, who have remained steadfast to the last, that I have consented to the result from no distrust of them…I determined to avoid the useless sacrifice of those whose past services have endeared them to their countrymen…I bid you an affectionate farewell.”— Robert E. Lee

1867: The United States Senate ratifies the treaty with Russia, that purchases Alaska for $7,200,000, or approximately $0.o2 per acre

1887: Anne Sullivan teaches the word “water” to Helen Keller.

1896: The first modern Olympic Games opens in Athens.

1904: Great Britain and France sign a mostly secret Entente Cordial which, although structured around their spheres of influence in their global empires, actually signaled the end of over a century of near-continuous hostility and occasional war between the two countries. Of more pertinence, the treaty solidified the obligations of one another against potential hostilities with the burgeoning Central Powers: Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy, also treaty-bound by their own Triple Alliance. By 1907 Russia grew increasingly concerned over the conduct of the Central Powers, particularly Austria-Hungary in the Balkans, leading them to join with France and Britain to create the Triple Entente. This process, my dear history students, is exactly what George Washington warned against when he spoke of the dangers of “entangling alliances,” as we shall see in July and August.

1912: Birth of Sonja Henie (d.1969),

1912: RMS Titanic sets out from Southampton, England on her first transatlantic voyage.

1913: Ratification of the 17th Amendment, specifying the direct election of Senators, a key political goal of the Progressive movement. Prior to this, Senators were appointed by state legislatures and represented the interests of the several States themselves, serving as a powerful check on Federal overreach. Given the scope of the federal government’s metastasis over the years since ratification, it is no surprise that there is a considered body of opinion exploring the ways the 17th may be repealed, not unlike how the 21st Amendment repealed the 18th a few days back.

1916: Two months into an

1917: The Canadian Corps of the British Expeditionary Force opens its attack on Vimy Ridge, a German controlled piece of high ground that dominated the northern area of the British Arras Offensive. The four day battle achieved its objectives against ferocious resistance, and its all-Canadian nature became a nationalistic touchstone for our northern cousins.

1939: Contralto Marian Anderson sings an Easter concert on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial before a crowd of over 75,000, plus a nation-wide radio audience. The critically acclaimed concert came about after the D.A.R. refused to allow her to perform in their Constitution Hall. Anderson went on to a sterling career as a classical singer both here and in Europe, and was one of the leading lights of the post-war civil rights movement.

1940: Norwegian politician Vidkun Quisling seizes control of the Norwegian government as the Nazi invasion tightens its grip on the country. He forms a collaborationist, pro-Nazi puppet government, serving as Minister-President under the control of the Germans. After the war, he is convicted and executed for high treason, and his name has become synonymous with “traitor” ever since.

1947: Jackie Robinson opens his major league career with the Brooklyn Dodgers.

1959: NASA announces the first corps of United States astronauts, seven test pilots from the Navy and Air Force, who will be at the pointy end, literally, of America’s first steps into outer space. If you were sentient at the time, you remember the absolutely riveting levels of national pride these guys engendered, and they had yet to actually do anything except pass an excruciating set of physical and psychological screenings. But there they were: our Mercury 7 Astronauts. Author Tom Wolfe captures the mood beautifully in his book, The Right Stuff (1979), and maybe even more so in the 1983 movie of the same name.

1962: Civilian test pilot Neil Armstrong takes the X-15 rocket plane to180,000 feet altitude.

1963: On a test dive after a hastily completed major overhaul, USS Thresher (SSN-593) sinks 220 miles off of Cape Cod with the loss of all hands (112 crew and 12 civilian).

1965:

1981: Death of General Omar Bradley (b.1893), USMA class of 1915.

1991: Georgia, the home of Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin, declares its independence from the collapsing Soviet Union.

As to the Swiss, a unique nation, in FEDERALIST No. 19, The Insufficiency of the Present Confederation to Preserve the Union, for the Independent Journal to the People of the State of New York by Alexander Hamilton and James Madison, mention is made of them, as follows:

The connection among the Swiss cantons scarcely amounts to a confederacy; though it is sometimes cited as an instance of the stability of such institutions.

They have no common treasury; no common troops even in war; no common coin; no common judicatory; nor any other common mark of sovereignty.

They are kept together by the peculiarity of their topographical position; by their individual weakness and insignificancy; by the fear of powerful neighbors, to one of which they were formerly subject; by the few sources of contention among a people of such simple and homogeneous manners; by their joint interest in their dependent possessions; by the mutual aid they stand in need of, for suppressing insurrections and rebellions, an aid expressly stipulated and often required and afforded; and by the necessity of some regular and permanent provision for accomodating disputes among the cantons.

end quotes

Then again, in FEDERALIST No. 43, The Powers Conferred by the Constitution Further Considered, for the Independent Journal to the People of the State of New York by James Madison, further mention of the Swiss is made as follows:

Protection against domestic violence is added with equal propriety.

It has been remarked, that even among the Swiss cantons, which, properly speaking, are not under one government, provision is made for this object; and the history of that league informs us that mutual aid is frequently claimed and afforded; and as well by the most democratic, as the other cantons.

end quotes

So consideration of the Swiss is certainly a part of our political history.

As to the Battle of Näfels, which was fought on 9 April 1388, long before there was a United States of America, it was a battle fought between the canton of Glarus, a canton in east central Switzerland, with its allies the Old Swiss Confederation, and the Habsburgs.

As to the Old Swiss Confederacy, it was a loose confederation of independent small states within the Holy Roman Empire which formed during the 14th century, from a nucleus in what is now Central Switzerland, expanding to include the cities of Zürich and Berne by the middle of the century.

Getting back to Glarus, according to legend, the inhabitants of the Linth Valley were converted to Christianity in the 6th century by the Irish monk Saint Fridolin, the founder of Säckingen Abbey in what is now the German state of Baden-Württemberg, and from the 9th century, the area around Glarus was owned by Säckingen Abbey, the town of Glarus being recorded as Clarona.

By 1288, the Habsburgs had claimed all the abbey’s rights.

In the meantime, from the early eighth century, Allemanic Germans, known to history as Alemanni or Suebi, who were a confederation of Germanic tribes on the Upper Rhine River moved into the valley.

As we who study history as the story of mankind recall, the Alemanni were first mentioned by Cassius Dio in the context of the campaign of Caracalla of 213, where the Alemanni captured the Agri Decumates in 260, and later expanded into present-day Alsace, and northern Switzerland.

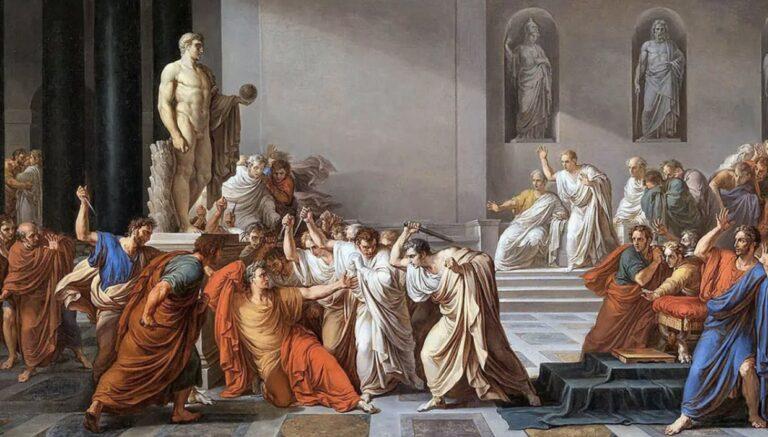

As to Caracalla or Marcus Aurelius Severus Antoninus Augustus, 4 April 188 – 8 April 217, formally known as Antoninus, he ruled as Roman emperor from 198 to 217 AD.

He was the elder son of Septimius Severus and Julia Domna and co-ruler with his father from 198.

After the death of his father in 211, he had his brother and co-ruler Geta killed, so that Caracalla reigned afterwards as sole ruler of the Roman Empire, a reign that featured domestic instability and external invasions by the Germanic peoples.

In 216, Caracalla began a campaign against the Parthian Empire, but he did not see the campaign through to completion due to his assassination by a disaffected soldier in 217.

So much for Caracalla.

In 496, the Alemanni were conquered by Frankish leader Clovis and incorporated into his dominions.

Getting back to the Battle of Näfels, it was the last battle of the Swiss-Austrian conflicts that stretched through most of the 14th Century.

A few weeks after the Battle of Sempach on 9 July 1386, the Old Swiss Confederation attacked and besieged the Habsburg village of Weesen on the Walensee.

The Battle of Sempach was fought on 9 July 1386, between Leopold III, Duke of Austria and the Old Swiss Confederacy, and the battle was a decisive Swiss victory in which Duke Leopold and numerous Austrian nobles died.

That victory in turn helped to turn the loosely allied Swiss Confederation into a more unified nation and is seen as a turning point in the growth of Switzerland.

As to that battle, during 1383 and 1384, the expansion of the Old Swiss Confederacy collided with Austrian interests.

In January 1386, Lucerne expanded its sphere of influence by entering pacts with a number of towns and valleys under Austrian control, including Entlebuch, Sempach, Meienberg, Reichensee and Willisau, and it was that move which was the immediate cause of war.

Duke Leopold gathered his troops at Brugg, consisting of his feudal vassals from Swabia, the Alsace, Aargau, Thurgau, Tyrol, as well as bourgeois forces of various towns and Italian, French and German mercenaries.

In the course of a few weeks, no less than 167 noblemen, both secular and of the church, declared war on the Swiss.

The gathering of Austrian forces at Brugg suggested an intended attack on Zürich, and the Confederate forces moved to protect that city, but Leopold marched south, to Zofingen and on to Willisau, apparently with the intention of ravaging the Lucerne countryside and perhaps ultimately aiming for the city of Lucerne, in what was known back in those times as a chevauchée, which was a raiding method of medieval warfare for weakening the enemy, primarily by burning and pillaging enemy territory in order to reduce the productivity of a region, as opposed to siege warfare or wars of conquest, and for that purpose, the Austrian army had a troop of mowers with them with the purpose of cutting down the corn and destroying the harvests along their route.

The town of Willisau was plundered and burned, and the army moved on to Sursee on Lake Sempach, and thence towards Sempach on 9 July.

Leopold’s men taunted those behind the walls of the town, and a knight waved a noose at them and promised them he would use it on their leaders.

Another mockingly pointed to the soldiers setting fire to the ripe fields of grain, and asked them to send a breakfast to the reapers.

From behind the walls, there was a shouted retort: “Lucerne and the allies will bring them breakfast!”

Confederate troops of Lucerne, Uri, Schwyz and Unterwalden had marched back from Zürich once it became clear that this was not Leopold’s target.

The forces of Zürich had remained behind defending their own city, while those of Bern had not heeded the confederate call for assistance.

In that battle, the Confederation army hoped to catch Leopold still at Sempach where he could be pressed against the lake, and around noon, the two armies made contact about 2 km outside of Sempach, which was to the mutual surprise of both armies, which were both on the move and not in battle order.

The Swiss held the wooded high ground close to the village of Hildisrieden, and since the terrain was not deemed suitable for a cavalry attack, Leopold’s knights dismounted, and because they did not have time to prepare for the engagement, they were forced to cut off the tips of their poulaines which would have hindered their movement on foot.

The Swiss broke through the Austrian ranks and routed the enemy army completely and Duke Leopold and with him a large number of nobles and knights were slain, including several members of the noble families of Aarberg, Baldegg, Bechburg, Büttikon, Eptingen, Falkenstein, Hallwil, Reinach, Rotberg and Wetter.

The following year, Glarus rose up against the Habsburgs and on 11 March 1387, the valley council declared itself free of Habsburg control.

In response, on the night of 21–22 February 1388, an Austrian army attacked the village of Weesen and drove off the Swiss forces, and in the beginning of April, two Austrian armies marched out to cut off Glarus from the rest of the Confederation.

The main army, with about 5,000 men, marched toward Näfels under the command of the Graf Donat von Toggenburg and the Knight Peter von Thorberg, and a second column, with about 1,500 men under the command of Graf Hans von Werdenberg-Sargans, marched over the Kerenzerberg Pass.

On 9 April 1388 the main army, under Toggenburg and Thorberg, attacked and captured the wall across the valley around Näfels.

The garrison, comprising about 400 Glarner troops and a few dozen troops from both Schwyz and Uri, held out for a short time, but was forced to withdraw into the hills.

As they retired, the Austrian army spread out to plunder the villages and farms, and the Glarners now emerged from the snow and fog to take the Austrians by surprise as they were preoccupied with looting.

Following a brief battle, the disorganized Austrians broke and fled toward Weesen, but the collapse of the bridge over the Maag or Weeser Linth dropped much of their army into the river where they drowned.

And such is history made.