“The coming disruption may be most disruptive to the work force in a hundred years. We see the kindling accumulating. It’s hard to know what the spark is that (starts the fire), we expect it to build up over the next decade – Karen Harris, managing director of Bain’s Macro Trends Group.

For many economists, wages, and not jobs themselves, are the key issue.

Turn-of-the-century London Workhouse (Image wikipedia)

According to economists like Ms. Harris, new technology and automation may create a long, deep economic disruption lasting decades and taking millions of jobs. The economy will eventually come out of it. But wages for most jobs may be too low to sustain a middle-class lifestyle.

Note: In the 19th century, it took about six decades for U.S. wages to recover after the first industrial age automation of the 1810s. And the agriculture-to-industrial shift of the 20th century lasted four decades.

Karen Harris forecasts that the new automation wave could displace 2.5 million workers a year.

“I’ll start to calm down when old-fashioned middle class jobs come back. I’m just not seeing that” – MIT’s Andrew McAfee, co-author of The Second Machine Age. Companies are not creating the middle-class jobs that were the backbone of the economy for more than a half-century. “We don’t have a job quantity problem, but a job quality problem,” McAfee said (NY Times).

Already, we are seeing wage disparity is increasing. Economists at the Brookings Institute note that automation will affect everyone, but will create more problems for different groups — young people perhaps, those less educated, groups that already receive less training and less education.

“We can stipulate that given human history and adaptability, we can have a phenomenal future…but transitions are always challenging. Given where we are starting today, given inequality, changes in geopolitics, it’s hard to see a turbulent-free transition to this brighter future” – Karen Harris.

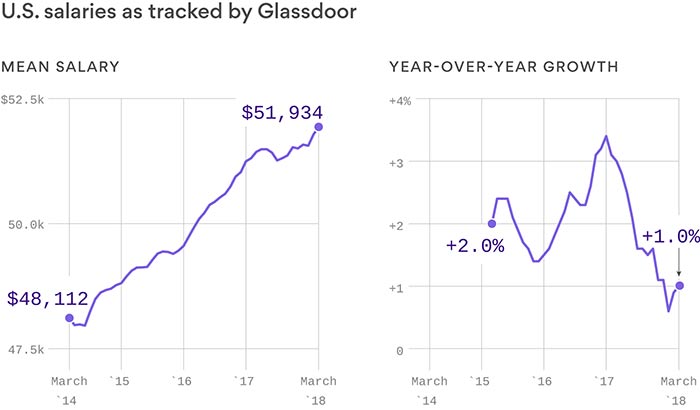

Glassdoor data, based on a survey of 100,000 salaries posted by the jobs site every month, shows very slow growth, shrinking to just 1% last month.Wages should be rising an average of 3%–4% given the tightness of the job market, but according to official data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, wage growth was a lower 2.6% in February.

Glassdoor economists attribute the stagnation to poor growth in productivity. If worker productivity is rising as measured by what’s made each hour, ordinarily wages should rise because they can charge more for their labor. However, hourly productivity is not rising, and neither are wages.

Discover more from CAPE CHARLES MIRROR

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Leave a Reply