New studies show that real estate markets are responding to increased flooding risks by reducing prices of vulnerable homes.

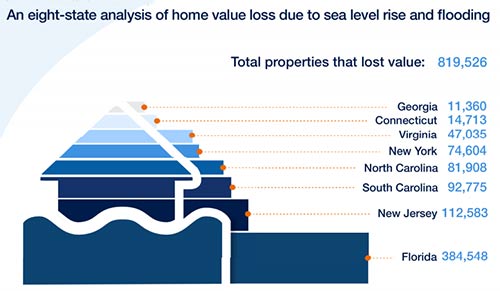

According to a report by the nonprofit First Street Foundation, housing values in New York, New Jersey and Connecticut dropped $6.7 billion from 2005 to 2017 due to flooding related to sea level rise. Combined with their prior analysis of 5 southeastern coastal states with $7.4 billion in lost home value, the total loss in 8 states since 2005 has been $14.1 billion.

Discover more from CAPE CHARLES MIRROR

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Washington Post just had an article on this subject entitled “Sea level rise is already costing property owners on the coast” by John Tibbetts and Christopher Mooney on 21 August 2018, as follows:

CHARLESTON, S.C. —Elizabeth Boineau’s 1939 Colonial sits a block and a half from the Ashley River in a sought-after neighborhood of ancient live oaks, charming gardens and historic homes.

A year ago, she thought she could sell it for nearly $1 million.

But after dropping the price 11 times, Boineau has decided to tear it down.

In March, the city’s Board of Architectural Review approved the demolition — a decision not taken lightly in Charleston’s historic district.

“Each time that I was just finishing up paying off the bills, another flood would hit,” Boineau said.

Boineau is one of many homeowners on the front lines of society’s confrontation with climate change, living in houses where rising sea levels have worsened flooding not just in extreme events like hurricanes, but also heavy rains and even high tides.

Now, three studies have found evidence that the threat of higher seas is also undermining coastal property values as home buyers — particularly investors — begin the retreat to higher ground.

On a broad scale, the effect is subtle, the studies show.

The sea has risen about eight inches since 1900, and the pace is accelerating, with three inches accumulating since 1993, according to a comprehensive federal climate report released last year.

By comparing properties that are virtually the same but for their exposure to the seas, researchers at the University of Colorado at Boulder and Pennsylvania State University found that vulnerable homes sold for 6.6 percent less than unexposed homes.

The most vulnerable properties — those that stand to be flooded after seas rise by just one foot — were selling at a 14.7 percent discount, according to the study, which is set to be published in the Journal of Financial Economics.

The study found the drop in prices appears to be driven primarily by investors buying multiple properties or second homes.

Such buyers tend to be wealthier and better educated than owners who occupy their coastal homes, said Ryan Lewis, an assistant professor of finance at the University of Colorado and a co-author of the study.

“Sophisticated buyers . . . demand a discount to bear the risk of future sea level rise,” Lewis said in an email.

The most-studied market has been Miami-Dade County, parts of which have for years been experiencing regular sunny-day flooding.

In a separate paper published in April, researchers at Harvard University found that properties at higher elevations were appreciating faster than properties at lower elevations, a phenomenon they dubbed “climate gentrification.”

Last month, the nonprofit First Street Foundation released the first analysis to single out Charleston, a gracious port city founded in 1670.

The analysis suggests that exposed homes in Charleston have lost $266 million in value since 2005 because of coastal flooding and expectations of still higher seas.

(Using the same method, the First Street researchers found a $465 million loss in Miami-Dade County.)

Harvard’s Jesse Keenan, who worked on the climate gentrification study, said the research is “an emerging area” that has produced uneven results.

For instance, the Colorado-Penn State study found lower property values along the U.S. coast as a whole and in several states, including New York, New Jersey, Florida and Massachusetts.

But it did not detect a change in South Carolina.

In addition, the overall effect on prices appears to be surprisingly small, said Susan Wachter, a professor of real estate at the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania.

“You could turn it around, almost,” Wachter said.

“Despite all the discussion of sea level rise, and despite the tremendous increase in the number of events over the last years and the destructiveness of the events, coastal building continues and coastal property appreciation continues.”

Indeed, beachfront property is not necessarily declining in value.

Rather, the studies suggest that more-exposed properties — including properties that have not yet experienced direct flooding — simply are not appreciating as rapidly as their inland neighbors.

Home prices on the coast are “going up along with market trends.”

“They’re just not going up as fast as other places,” said Jeremy Porter, a Columbia University researcher who conducted the First Street study with Steven McAlpine, the group’s head of data science.