Sometimes it’s just great to see chickens having fun. One of Karen Davis’ favorite things is watching her chickens jump for joy (bread!). This brief audio-video captures one of those moments. It’s not just any bread. It’s Ezekiel flour-free grains & seeds – their favorite!

Great Dogs at Eastern Shore Regional Animal Control Facility Need Your Help

This week’s URGENT available dogs! If you cannot help by adopting or pulling for rescue ask around and share this information on the Eastern Shore Regional Animal Control Facility Facebook page. The more views these animals get the better chance they have of finding homes.

Everyone is through their hold and ready to find new loving homes.

These dogs are loving and friendly, and just want someone to bring them home.

Call (757) 787-7091 or email accomackanimalcontrol@gmail.com

If you see a sweet face that you would like to change their life and show them what a family and good home is supposed to be please send us a message and we will be happy to assist you in the adoption process.

All of these dogs are urgent, and limited time now that their hold is up! It is very important to us to save as many of them as possible! We can only do that with the help of adopters and rescues to pull them out of the facility and into new happy lives

Details that we have on each dog will be on the picture descriptions! If you have any other questions please reach out to us!

Pet of the Week: Addie Still Needs a Forever Home

Hi, I am Addie, a hound mix at around 3 years old and about 48 pounds. I like to dig, and I really appreciate love and affection. I have some dogs I seem to get along with all right so far, but not sure how I would do with cats. I seem to like people of all ages and enjoy the couch in the lounge when the volunteers socialize me.

I enjoy leash walking and love treats. I seem to have maintained my potty training from my days in a home.

If you think you may be interested in adopting Addie, you can stop by Tuesday-Saturday 10 a.m.-2:30 p.m., do a kennel walkthrough, and pick up an application while you are there.

You can print out an application on our website anytime at www.shorespca.com . You can also email us at shorespca@gmail.com and ask that an application be attached and sent back to you or call the shelter anytime with questions at 757-787-7385.

Pet of the Week: Meet Spot

Hi, I am Spot, a 2-year-old German Shepherd/Husky mix. I weigh in at around 60 lbs. I am a friendly guy who doesn’t really like to be away from people for too long. I love attention and am very happy-go-lucky. I am fairly clean in my kennel.

Though at a glance I look very much like a Shepherd, closer inspection of my thick coat and blue eyes give away my Husky mixture.

I just kind of aim to please. I really enjoy socialization and may do well with another dog. It is unknown how I would do in a home with cats. Children of some size and age should do well with me around. I do have manners, and I usually listen pretty well.

If you’d like to see me, you can come to the shelter and do a walkthrough of the kennel between 10:00 a.m. and 2:30 p.m. Tuesday through Saturday. You could even pick up an adoption application while you’re there. Applications are also available online (www.shorespca.com) or can be obtained by calling the shelter (757-787-7385) or email to ask for one (shorespca@gmail.com).

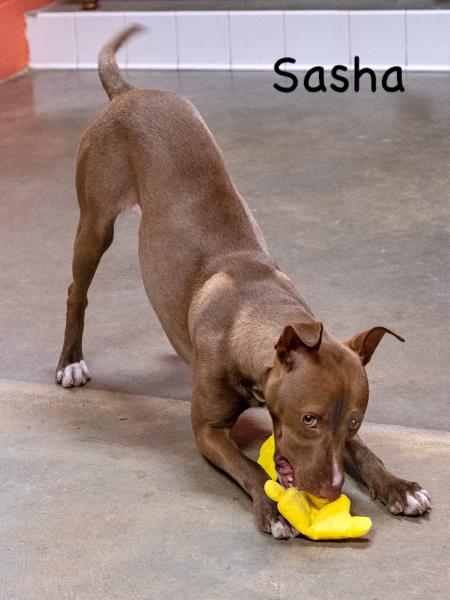

Pet of the Week: Meet Sasha

Hi, I’m Sasha. A female hound mix weighing in at just 21 lbs., I am around 10 months old. I’m not expected to get much bigger than I am right now.

I like being with people, and as you can see in my photos, I really enjoy toys. Tug of war is my favorite game! I am very full of youthful energy, so I’d benefit from a home with someone who will take me on walks to give me exercise and help me burn off some of my puppy steam. I bet you and I could have lots of fun together!

I’ve never lived in a house, so I will need some work on my house training, but I’m eager to learn if you’ll teach me. I’m all ready to go home with you because I’ve already been spayed and am up-to-date on all age-appropriate shots.

You can visit me at the shelter from Tuesday-Saturday between 10:00 a.m. and 2:30 p.m. In fact, you could even pick up an adoption application while you’re there (hint, hint)!

Applications are also available online at www.shorespca.com, or you can request one by email (shorespca@gmail.com) or by calling the shelter (757-787-7385).

United Poultry Concerns launches media campaigns in Atlanta and DC

United Poultry Concerns of Machipongo is delighted to share with you photos of their OutFront Outdoor Media posters displayed in 17 bus shelters in Atlanta, Georgia and 17 Bike Share locations in Washington, DC through the entire month of May in honor of our annual International Respect for Chickens Day May 4/month of May campaign.

Begun in 2005 to celebrate chickens throughout the world and protest their use in farming operations, and in all violent enterprises including cockfighting and laboratory experiments, International Respect for Chickens Day urges activists to do a special COMPASSIONATE ACTION for chickens in May and – needless to say – every day!

UPC gratefully accept tax-deductible donations to support our Outdoor Media posters in selected cities each year. $30,000 per city for one month brings our message to thousands of people – in May on behalf of Chickens, in November on behalf of Turkeys!

Atlantic blacktip shark considered fully recovered

Once overfished, the Atlantic blacktip shark population is now considered fully recovered—thanks in part to robust management measures implemented by NOAA Fisheries.

Blacktip sharks now account for approximately 60 percent of commercial and recreational catch of large coastal shark species—but that wasn’t always the case. In 1998, NOAA Fisheries determined blacktip sharks to be overfished and experiencing overfishing. To address this problem, we implemented management measures for commercial fisheries, including a reduced commercial quota for large coastal sharks and recreational size and bag limits.

This allowed Atlantic blacktip shark populations to successfully recover. In 2006, the blacktip shark population was split into Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic stocks for assessments; the Gulf of Mexico stock was determined to be no longer overfished. In 2018, the Gulf of Mexico stock had recovered enough to support four times the regional harvest. As of the final assessment in 2022, neither the Gulf of Mexico nor Atlantic blacktip shark stocks are overfished and overfishing is not occurring.

5 Fast Facts: Blacktip Sharks

1. Range

Blacktip sharks are commonly found in coastal waters from Virginia to Texas, but have been found as far north as Massachusetts. Each winter, blacktip sharks migrate south to Florida waters and then migrate back up the Atlantic coast in the spring by the thousands.

2. Life History

Female Atlantic blacktip sharks give birth to litters ranging from one to seven pups, with four pups being the average. By shark standards, blacktip sharks are fast growing and quick to mature, reaching reproductive size within 5 to 7 years. Atlantic blacktip sharks can live up to 17 years.

3. Behavior

Like their cousin, the spinner shark, Atlantic blacktip sharks are known for their acrobatic leaps into the air. They can spin up to three times before plunging back in the water!

4. Appearance

Spinner and blacktip sharks are difficult to tell apart as they have similar body shapes and black tips on most of their fins. The difference is the black tip on the spinner’s anal fin. Ironically, this is the only black tip that the blacktip shark doesn’t have!

5. Diet

Blacktip sharks typically feed on small schooling fish like herring, anchovies, sardines, and menhaden. Blacktip sharks are themselves food for larger sharks such as great hammerhead, tiger, and bull sharks.

Pet of the Week: Carter Still Needs a Furever Home

I’m Carter, and as of March 2023, I have spent over a year at the shelter with my friends at the SPCA Eastern Shore. It seems that in that year I have mostly been overlooked in the kennel. I’ve only had one meet and greet visit, and the senior female dog in that family decided she didn’t like me, so I didn’t get that chance to become part of a family.

I came to the SPCA Eastern Shore Regional Animal Control facility in April of 2022 when a nice lady found me running around and playing behind the Eastern Shore Community College. She put me in her car and drove me to this really neat building they called “Tractor Supply,” where I had a nice bath that I took like a champ.

I was then taken to the Animal Control building, but my owner never came forward, so I was transferred to SPCA Eastern Shore in March of 2022.

I’m getting close to 3 years old but am still very much a young handsome guy. In the year that I have been here my happy-go-lucky attitude has never wavered. Even though another dog hurt me really bad once, I am very forgiving and believe there still may be another dog out there I can get along with.

I seemed to mostly ignore cats when I was cat tested some months ago, although whether I’d get along in a home with cats is not certain. When it comes to people, I do not know a stranger. I seem to want attention and affection from them all.

I hear them say the SPCA Eastern Shore is a no kill shelter, whatever that means. Anyway, they say I have a home with them as long as I need one. Yet, I would love to see beyond the kennel walls and take nice long walks with people of my own. Maybe perhaps even sit next to them while they’re watching TV, although I might just turn my head back and forth in confusion since I don’t even know what a TV is.

I have a lot to learn, and I am eager to learn it. I am fairly clean in my kennel and love toys and blankets.

I am a very reliable guy, and you can always count on me to be very sweet.

Please call us to arrange a meet&greet with this sweet boy 757-787-7385.

Sea Turtles Finally Get Protection

AP story by JENNIFER McDERMOTT and ARNULFO FRANCO – On a Panamanian beach long after dark, a group of undergraduate students dug into the sand to excavate a sea turtle nest, their lamps casting a soft red glow as they studied eggs, inventoried the success of the hatch and checked for any surviving hatchlings stuck at the bottom of the nest. Nearby, armed members of the National Border Service stood watch for protection in an area known for drug trafficking.

The students worked under the guidance of Callie Veelenturf, who founded a group that works to protect leatherback turtles and pushed for a new law in Panama that guarantees sea turtles the legal right to live and have free passage in a healthy environment.

The new law “will allow any Panamanian citizen to be the voice of sea turtles and defend them legally,” Veelenturf said in a text message as she boarded a plane to Panama City after her group’s work near Armila. “We will be able to hold governments, corporations, and public citizens legally accountable for violations of the rights of sea turtles.”

When Panama’s president signed the law in March, it was a victory for people who have long argued that wild animals should have so-called rights of nature that recognize their legal right to exist and to flourish, and allow for lawsuits if those rights are violated. Experts hope it’s part of an evolution that will see other countries take similar steps to protect species under threat.

“Business as usual laws aren’t doing enough to protect against the extinction crisis and climate change,” said Erica Lyman, a clinical law professor and director of the Global Law Alliance for Animals and the Environment at Lewis & Clark Law School in Portland, Oregon. “This is an attempt at a new kind of framing that offers hope.”

Pet of the Week: Lolly Still Needs a Home

Lolly, a 10-year-old-plus female Foxhound, has been a resident here at the shelter twice before. We don’t know her history before she came to us for the first time, but we’re hoping that the third time’s the charm for her in finding her “furever” home.

Had we known what we know now about Lolly when she first stayed with us, we might have named her Houdini. When she was adopted, it turned out that she’s a master escape artist. True to her breed, given even the smallest chance to follow a scent, Lolly goes bounding joyfully off to investigate it. She walks on a leash, but whoever’s walking her needs to be ready and have a firm hand to control her when she picks up a scent and wants to bolt after it. We do not recommend Lolly in a home with cats.

Something we didn’t find out about Lolly during either of her previous stays at the shelter is that she’s apparently afraid of loud noises. One of the family members in her second adoptive home was wheelchair bound. During thunderstorms Lolly would run to her lap seeking comfort and reassurance. Concerned that Lolly might injure her, the family reluctantly returned Lolly to us.

So this lovely “lady of a certain age” obviously won’t fit easily into just any home. She needs an adopter who’s aware of her wandering ways and her fear of loud noises and is savvy enough to handle them. A home without a feline family member would probably be best because— well, Lolly’s a Foxhound; chasing small animals is In her genes. A securely fenced yard would be a bonus.

But in the right home, Lolly will make a delightful and loving companion. She likes people and gets along well with people of all ages. She’ll make herself right at home on your couch, and she loves getting belly rubs. She’s clean in her kennel here and is potty trained. And she’s already spayed and is up to date on all vaccines.

Think you might be the right match for Lolly? Come do a kennel walkthrough between 10:00 a.m. and 2:30 p.m. Tuesday through Saturday and get to meet her. If you’d like an adoption application, you can pick one up during your visit, download one from our website (www.shorespca.com), or request one by email (shorespca@gmail.com). You can also call the shelter between 10:00 a.m. and 3:00 p.m. if you have any questions.

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- …

- 30

- Next Page »